Fixing This

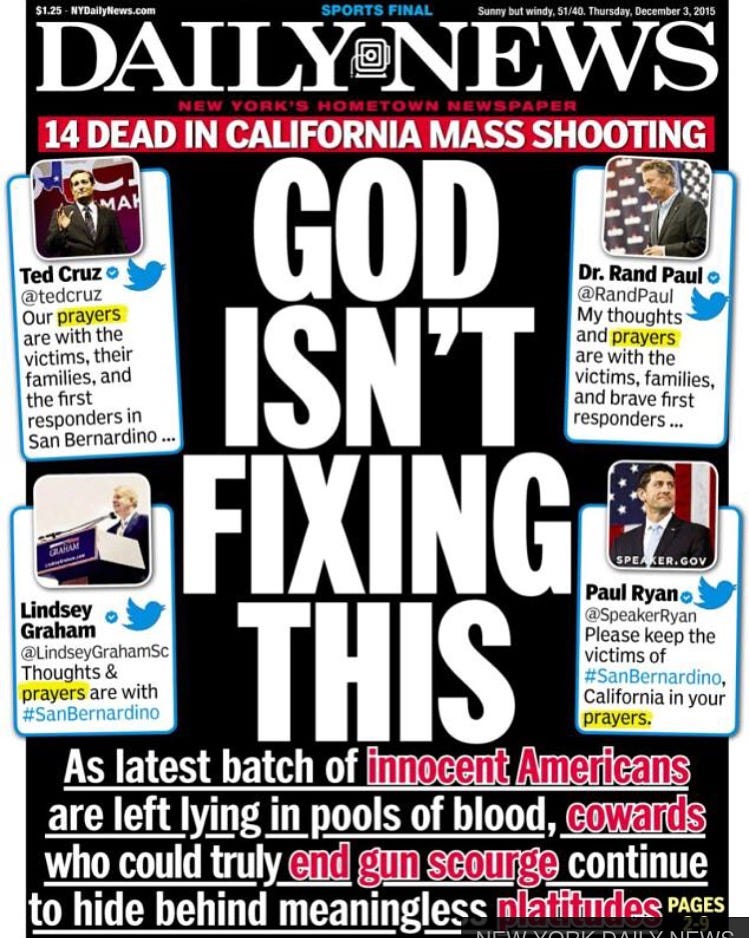

I was scrolling through my photo archive when I came upon this screenshot. This was the front page of the Daily News tabloid published on December 3, 2015, the day after a mass shooting in San Bernardino. Don’t remember it? I don’t blame you; I had to look it up, too.

Since this cover was published, there have been over 3,400 additional mass shootings in America. That’s 500 more than the number of victims of the 9/11 attacks. There was a mass shooting yesterday.

You could cover up any mention of location and this cover could have been for any shooting in the last eight years. Pulse nightclub. Monterey Park. Las Vegas. Uvalde. Parkland.

I think back on the version of myself from eight years ago. What was he thinking when he made this screenshot?

Even in 2015, this had felt like a kind of holding pattern, just circling above as the tank emptied. The country’s capacity to accept needless death appeared bottomless.

I wondered why we never saw real images of the shootings. Not cops standing around outside. Or sweaty politicians trying to sound serious in front of a podium. Or devastated family members holding it together long enough to reminisce about the ones they lost.

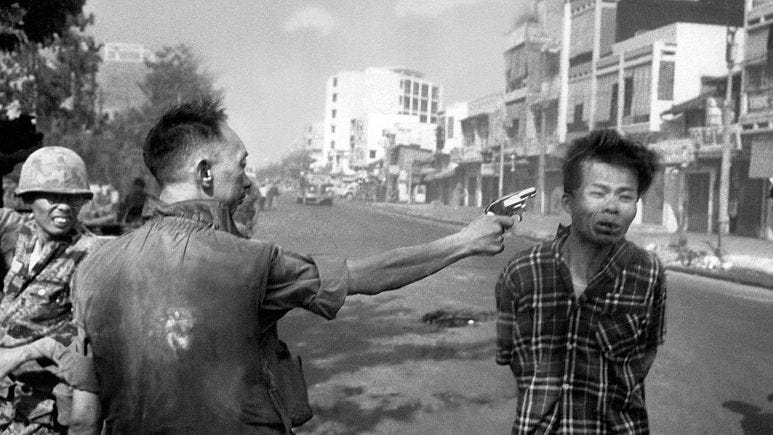

Images changed the way people saw conflict. A South Vietnamese general executes a prisoner at point blank range. A naked girl, severely burned and screaming, runs away from a napalm attack. These images shattered the illusion that America was fighting a moral battle and shifted public support for the Vietnam War.

Less graphic, perhaps, but the media was banned from recording images of flag-draped coffins being repatriated during the Gulf War. The reason given was to protect the privacy of families, but it also had the convenient effect of obfuscating the raw number of dead soldiers brought back from Iraq. With the proliferation of cameras, those in power knew that this kind of censorship was necessary to cover up realities that diverged from the one they preferred to present.

So why then does the media not show us the reality of mass shootings? Why do we never see the obliteration—mutilated flesh, shattered bone, exit wounds, blood spatter on ceiling and floor? What is the role of the media in filtering how we perceive these events? Does the media have a responsibility to give the people a full understanding of what took place? Is the media paralyzed by concerns of being perceived as exploitative and crossing some kind of aesthetic red line? These are not unique questions.

It’s clear that without something changing, the status quo will remain. Another shooting, followed by grief, boilerplate concerned tweets, spurts of televised debate, newsletter think pieces, then we go again. We can’t afford to just keep circling.